On the first Saturday in May, in the third year of the Great Plague, a fairy tale unfolded on a racetrack in Kentucky. A horse entered the Kentucky Derby literally at the last minute, after another horse was withdrawn, or scratched as they say in the business. He was sold from his breeding farm as a youngster, came in dead last in his first race, and was disposed of in a claiming race, where anyone who pays the set price can claim the horse. It’s a trope in horse novels, the driver of many a desperate plot, trying to save the horse from this sad fate either by keeping him out of the claiming race, or scraping up the funds to pay the price.

Once this horse was claimed, he ended up in a small-time stable as such things go, with a trainer who had never won a major race, and a jockey who had never ridden a horse at this level. No one expected him to do more than show up. All the attention was on the favorites, the stars with illustrious records and famous trainers.

Then came the race. It was presented as essentially a match race between two top horses, one of whom all the experts expected to win. The cameras focused on them. The announcer concentrated on them. The narrative was all about them.

And out of nowhere, threading the needle of the crowded field, came the 80 to 1 shot, the claimer from the no-name trainer with the jockey who had never ridden a top race. He surged past the leaders. And he won.

But like all fairy tales, this one has a darkness in its heart. There’s a ritual in big marquee races. After the finish, an outrider catches up with the winner and finishes the job of slowing him down, and a reporter on horseback comes to interview the jockey. The jockey’s job is to burble about his race, and the outrider’s job is to control the horse.

This time, it didn’t go according to script. The horse did not cooperate. He attacked the outrider, and he attacked the outrider’s horse, on national television and in video clips posted all over social media. And the outrider dealt with him in no uncertain terms.

Of course it went viral. The race itself was an instant legend, but the aftermath turned it into a headlong gallop to judgment.

One of my friends, in making their own judgment, called it Rashomon. Everybody had an opinion, and everybody saw something different. A meme went the rounds, pointing out that people who had never been nearer a horse than their television screens were now experts in racehorse handling.

The leaders in the Judgment Derby went in two directions. Geld the horse! And Fire the outrider! The back of the pack came up with all sorts of shoulds and why didn’ts. One strong faction maintained that such a horse should never have been allowed to exist, that all horses should be bred for kind temperaments, and aggressive stallions should invariably be gelded. Another faction insisted that if the horse had just been turned loose, or never restrained at all, he would have cantered nicely to the winner’s circle and all would have been well. And of course there was much condemnation of the outrider for striking the horse in the face.

Buy the Book

All the Horses of Iceland

The one faction that didn’t say all of these things was the one with actual experience of racehorses, and actual experience of stallions. This was a complicated situation, but not an unusual one. The only really unusual thing about it was that it happened in such a very public venue, in front of so many people, both on the track and in the media.

There were several realities in play on that day. Both horse and jockey had no experience of a crowd that size or a race that intense. The trainer had collapsed when the horse crossed the wire, until a pile of wildly overexcited people picked him up in celebration, so he didn’t see what happened.

But the cameras did. What I saw, from a quarter-century of handling stallions, was a three-year-old colt off his head with excitement, being a raving asshole to the horse and the human who were telling him he had to stop running now. That in fact is what the trainer said in an interview two days later. He thanked the outrider for preventing some very bad things from happening.

The outrider did exactly what he had to do in order to get the horse’s brain out of his back end and into his head, which at that point was not going to be anything resembling sweet or gentle. When a stallion of any age is in that frame of mind, you will have to clobber him, because nothing else will begin to get his attention.

Why didn’t he let the horse go? The trainer, who knows the horse’s racing brain very well indeed, explained that the horse was still in racing mode. He wanted to keep running, and he was both wired and trained to head for the front. There was not going to be any nice relaxing canter, not in that space or under those conditions. When a strange horse got in his way, his instinct was to lunge at the horse and make him move. Stallion fight, leading with teeth and doing his best to rear up and batter with forefeet. People who saw blood on his face accused the outrider of tearing him up, but the blood was not his. It was the other horse’s.

The only reason it wasn’t the outrider’s was because the man was wearing sturdy clothes. He was bitten badly on the leg and arm. A horse’s bite is extremely strong. It’s like being clamped in a vise. And then it tears. A horse in a rage can literally rip a human’s arm off.

That’s what the Let Him Free faction wanted turned loose in a crowded area with many humans on foot and a number of horses. At best the horse would have trampled some of those humans. At worst, he would have attacked another horse, or run into the walls or injured himself trying to get away. Instead, there was a short struggle, it got sorted, the horse settled down, the outrider did his job of leading the horse to the winner’s circle.

Where was his jockey through all this? A jockey perches high on a very flat saddle, designed to keep him out of the horse’s way as much as possible. His job is to pilot the horse around the track, control his speed while he’s in motion, and reel him in at the end, but with care, because racehorses are trained to run faster under rein pressure. If the horse had taken off and started crashing into people and objects, the jockey most probably would have been thrown. And the horse might have between completely out of control. A racehorse in that mode has no concern whatsoever for his own safety or for the life or limb of anything around him. He would literally bolt off a cliff if that was where he was headed.

The outrider did his job. Yes, it was ugly. And yes, the horse was being an ass.

So what about that temperament? Isn’t it terrible? Why do people let such stallions exist?

Because they win races. Rich Strike was bred to race. That’s what he’s for. He is not meant to be a nice, cooperative riding horse. He is meant to run very very fast and win a great deal of money, and when he’s done enough of that, he’ll go where the real money is, which is onto the breeding farm, collecting six-figure stud fees and siring horses who will also, their breeders hope, run very very fast and win much much money.

Here’s where writer brain comes into play. I have my own thoughts about an industry that churns out thousands of horses in search of that tiny handful of big winners, and I certainly do have thoughts about babies put under saddle and put in serious training at ages when they’re just barely into adolescence. Rich Strike at just three is at the age when the hormones just really start to come in. He’s a 14-year-old boy in the body of a thousand-pound, living torpedo.

Here’s a video of stallions from a breed actually bred for temperament, who are the same age as Rich Strike. Two herds, aged two and three, are put together into a larger herd. See how they interact? Now look at pictures of wild stallion fights. See what they do? Rich Strike was doing what came naturally. And in that situation, there were very few safe options and very little time to pick one.

Yes, for his own safety in future races, he needs to learn how to behave after a race. But he’s not on this earth to be a nice riding horse. He’s not a pet or a companion. He’s an elite athlete with a very narrow and incredibly lucrative purpose.

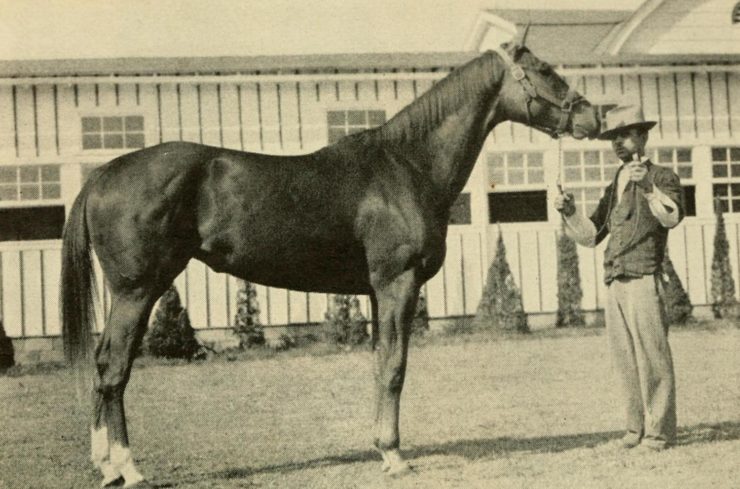

You could not pay me to handle a horse like this. Even the groom who loves him is not shown holding him with a plain halter or a simple lead. In photo after photo, that horse is under strong restraint, with some form of metal in his mouth or around his head. That is nothing resembling a tame lion. What he is is a horse who just won over a million dollars, who will be entered in another, longer, equally lucrative race, and who will go on to make incredible amounts of money in the breeding shed.

I know how I feel about that, personally and from my own herd of horses bred for temperament and trainability, with my sweet stallion (who still gets mouthy and sometimes goes Up) and my warrior mares. But as a writer and horse person, I understand what he is and what he’s for. I get what the outrider did and why. He did it to protect the horse and everyone else in that chaotic space–and he did it at considerable cost to himself and the horse he was riding.

It’s a fairy tale. Exhilarating. Startling, in both good and bad ways. Messy and complicated and not at all straightforward or simple. But it has its own logic. It makes sense within its own particular corner of the universe.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks. She’s written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.